'A story of love, war, and peace'

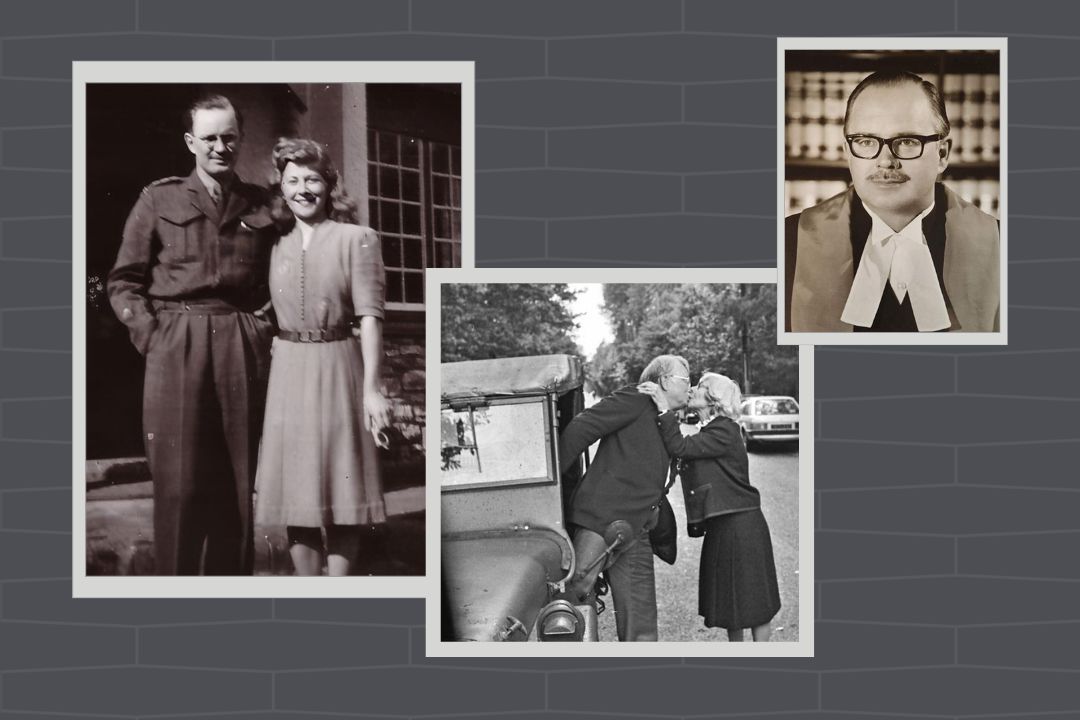

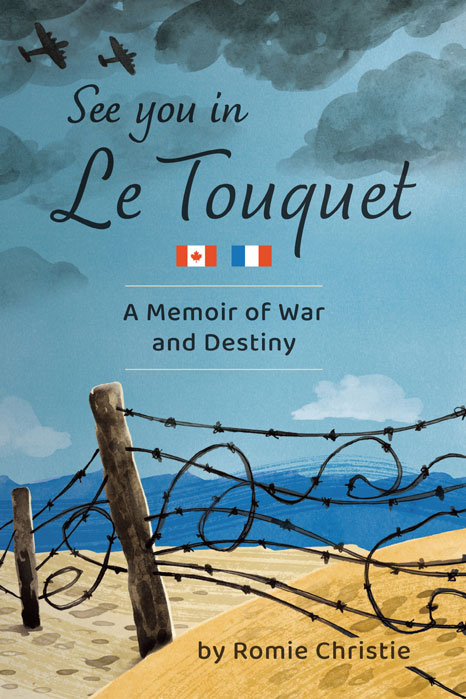

As a Canadian soldier in Europe during the Second World War, USask graduate Capt. Sandy MacPherson (LLB’38) met the love of his life in a dramatic moment in Le Touquet, France.

By Shannon Boklaschuk

“Theirs is a story of war, love, and peace. A story for the ages.”

That’s how former Canadian journalist Romie Christie describes the captivating lives of her late parents, University of Saskatchewan (USask) graduate Sandy MacPherson (LLB’38), and his wife, Dorothy (Borutti) MacPherson, who fell in love amongst the conflict, suffering, and challenges of the Second World War.

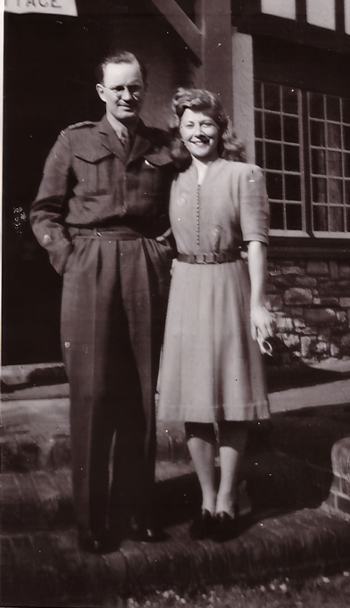

Christie has captured their fascinating story in a 2023 book, See You in Le Touquet: A Memoir of War and Destiny. Published by Regina’s DriverWorks Ink, Christie’s book explores her parents’ personal journals as well as family stories and historical records.

“Without question, their first meeting is quite a story. A story worth telling. A story I’ve told numerous times throughout my life. Many people know or have heard it. Even former Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, who appointed my dad to the Court of Queen’s Bench in Saskatchewan, once described it as ‘the best love story ever,’ ” Christie wrote in the book’s preface.

“But in truth, it’s so much more than a love story. It’s about a young man and a young woman from different parts of the world who lived through the same long war. Each experienced their own adversities, traumas, and challenges. Each was forced to find their own resilience and strength. Until their lives finally intersected.”

Sandy MacPherson's early life

Sandy MacPherson was born on Nov. 15, 1916, in Swift Current, Sask. He was given the full name of Murdoch Alexander MacPherson, Jr. by his mother, Iowa, in honour of his father—who was also named Murdoch but was more commonly called Murdo.

Murdo, the eldest of six children, was born in 1891 on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. He had received a scholarship to attend Dalhousie University in Halifax, graduating with a law degree from the university in 1913. Murdo relocated to Saskatchewan when a law firm in Swift Current offered him a job. It was in Swift Current where Murdo met and married Iowa—and Sandy subsequently spent an early part of his childhood—during the First World War. Murdo, who had served in the war, returned to Canada, and to his family, with serious injuries.

“In Sandy’s first conscious memory, he was sitting in the windowsill of the new apartment he and his parents had just moved to in Swift Current during the summer of 1919,” Christie wrote.

“Sandy was a few months away from turning three. His knees were tucked under his chin as he watched a column of repatriated men marching below, a cheering crowd standing on either side. These men were returning from the war, healthy and strong. But his father was not with them.

“Murdo’s injuries would never allow him to march again. In fact, his lingering disabilities left Murdo in a quandary. He was eager to get back to practicing law, to advocacy and defending people in the courtroom, but that wasn’t the kind of legal work he could do sitting down. Getting up the stairs at the courthouse was problem enough. Moving around the courthouse as a trial lawyer on crutches was an impossibility. How was he to support his family?

“Fortunately, a solution landed in his lap. Murdo took an appointment as the solicitor to the Soldiers’ Settlement Board in Regina, the capital city of Saskatchewan 245 kilometres east of Swift Current.”

As a result of his father’s new job, Sandy and his family moved to Regina. As he grew up in the city, Sandy excelled as a student. After graduating from Central Collegiate, he decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and study law.

“He was a really smart guy, I would say. He was a real intellectual,” Christie recalled in a recent interview with the Green&White. “He was not particularly athletic, although he loved watching baseball and sports. He was a major reader; he read all his life. He graduated high school when he was 16 and he was just really pretty smart—I think almost smarter than he realized.”

Going to war

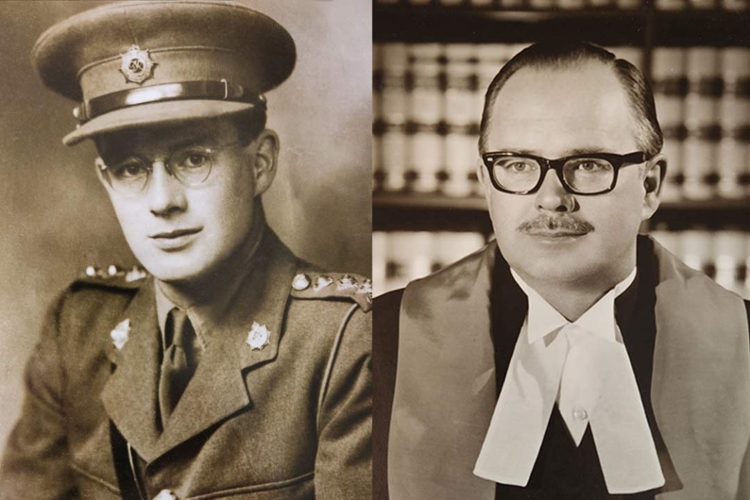

In May 1940, then 23-year-old Lieutenant Sandy MacPherson, wearing a new military uniform, arrived by plane at the Regina airport to say goodbye to his family before being shipped over to Britain. At the time, his brother, Ian, was completing his second year at the Royal Military College in Kingston, Ont. When asked by his family where he would be stationed, Sandy replied that “We’re to serve as backup to 1st Division. Beyond that, we have few details.” It was an emotional time. As Sandy prepared to leave his family, his brother Donald MacPherson—who would later earn a Bachelor of Laws degree at USask in 1948—asked to see Sandy salute.

“Sandy smiled, lifted his arm impeccably, his feet held tightly together,” Christie wrote. “Then in a split second, he reached down, tossed Donny the baseball mitt sitting on the stoop, and threw the ball high in the air. He and his younger brother had often played together during the previous summer. The family cheered at Donny’s perfect catch. ‘I must savour every minute of this time,’ Sandy promised himself.”

Adjusting to life in the army was difficult for Sandy, who, like so many soldiers, experienced loneliness and homesickness. He didn’t know it then, but at the same time he was in England, his future wife, Dorothy Borutti, was living in Le Touquet, France, under Nazi rule. On Jan. 3, 1941, following a bleak and dismal Christmas season, Dorothy turned 19 years old. It was a challenging time for her family and for the other residents of Le Touquet, who had no choice but to adapt to their new reality.

“With the arrival of the new year, the Touquettois adjusted as best they could,” Christie wrote. “Some local services continued to operate, especially those needed by the German occupiers, such as electricians, bakers, carpenters, and car repair shops. Despite the fact that many local men were now in German prisons or work camps, the remaining residents had little choice but to participate in an uneasy truce, though no one forgot who held all the power.

“Nazi rules were tough. Everything was rationed, curfews were strictly enforced, everyone was hungry. And given its geographical location, Le Touquet was in the forbidden coastal zone, so control was more severe there than anywhere else in France.”

Sealed with a kiss

As the war continued, Sandy, Dorothy, and their family members faced many hardships. At one point Dorothy found herself imprisoned in Lille, France, for listening to the English radio. Meanwhile, her future husband, Captain Sandy MacPherson, was working tirelessly in Britain to create a more just court martial system for the Canadian army. As she sat in her jail cell as a political prisoner, Dorothy vowed that she would embrace the first liberator who came to free her and her hometown of Le Touquet.

In the recent interview about her book, Christie said it seemed like destiny that her parents would one day meet in Le Touquet. She noted that Sandy was always an avid reader, and as a youth one of his favourite authors was P.G. Wodehouse—who happened to live in Le Touquet until the German occupation in 1940, during the war. It’s perhaps not surprising, then, that as the army eventually made its way north in France to the town of Montreuil, close to the town of Le Touquet, Sandy decided to visit.

“That’s where P.G. Wodehouse had been captured by the Nazis, and my dad had read about the town—something drew him there,” Christie said. “He took a Jeep and a couple of guys went with him to drive over and see what was left of Le Touquet."

As Sandy and the other Canadian officers drove along an avenue in Le Touquet, marked by a large square that featured seriously damaged hotels, Sandy spotted something unexpected up the road: a young woman—Dorothy—jumping up and down and waving her arms. Sandy shouted to the driver of the Jeep to slow down and stop. It was a life-changing moment.

“Lo and behold, she ran right up to him, stood on her toes, reached her hands onto his shoulders, angling him down towards her, and she kissed him. A real kiss, right on his lips,” Christie wrote. “Dorothy was just as stunned and thrilled as Sandy. She’d done what she’d vowed she would do! She’d kissed the first Allied solider she saw. A real, lip-smacking kiss.”

Making a life together

After that fateful day, Sandy and Dorothy knew they were meant to be together. On April 2, 1945, Dorothy Borutti officially married Sandy MacPherson in Le Touquet during a morning ceremony at City Hall—a building that had somehow survived the bombings. The war ended shortly after, and Sandy and Dorothy moved to Canada to begin their life together in Saskatchewan.

“Before they had been officially married, Sandy had come clean about the weather in Saskatchewan,” Christie wrote. “He’d told her that upon a winter arrival in Regina, the temperature would likely be 20 degrees below zero with a howling wind. She had laughed at the time and had chosen not to believe him. But she wasn’t laughing when they disembarked from the train in Regina. She’d never felt that kind of biting cold on her face.”

When Dorothy moved to Canada, she vowed to love her new country while continuing to be a strong ambassador for her homeland of France. Sandy’s family quickly embraced Dorothy and welcomed her to her new home.

“Dorothy already loved Canadians for what they’d done to free France. Regina was very different from Le Touquet, yet people couldn’t have been kinder or more welcoming,” Christie wrote.

Just over two years after they wed, Sandy and Dorothy welcomed their first son in May 1947. He was named Ian, in honour of Sandy’s brother who passed away during the war. Their first daughter, Rosemary (Romie), was later born in 1950, and their second daughter, Alexandra, arrived in 1955. In Regina, Sandy became a partner with his father’s law firm, MacPherson Leslie and Tyerman, while Dorothy befriended women in the community. The MacPhersons enjoyed a vibrant social life in Regina, filled with evenings of dancing and music.

In 1961, Sandy’s father, Murdo, was awarded an honorary Doctor of Civil Law degree during USask’s Spring Convocation. That same year, Sandy was appointed as a Justice of the Saskatchewan Court of Queen’s Bench, where he served for two decades until his retirement in 1981 at the age of 65. He presided over many interesting cases, including a notorious murder trial that involved the 1967 killing of a farm family near Shell Lake, Sask.

“Throughout his career, Sandy developed an excellent reputation, which journalist and author Jack Batten wrote about in his book Judges. Batten said Sandy was ‘probably the most respected trial judge in his generation of Saskatchewan jurists,’ ” Christie wrote.

“Another author, Maggie Siggins, also wrote about Sandy in her book A Canadian Tragedy: JoAnn and Colin Thatcher: A Story of Love and Hate. She said that Sandy ‘developed an expertise for trials that involved massive amounts of detailed information,’ and she quoted Regina lawyer Gerry Gerrand as saying, ‘I’ve always felt that MacPherson was, if the not the best, one of the best, trial judges during the past decades.’ ”

During his retirement, Sandy learned how to type and began writing down his memories and recounting his experiences from the Second World War. While Sandy never published those essays and chapters into a book, he passed them on to Christie about a decade before he died. Christie, who lives in Calgary and had worked with CBC Radio for about 20 years, hoped to one day do something with her father’s papers. After Christie retired in 2019, and while the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the globe in 2020, she decided the time was right to write her parents’ story.

“I realized at that point if I didn’t write this story, it would be gone. It would just fade away like most family stories do, and it was such a good story—the parts that I knew,” she said.

Returning to Le Touquet

Throughout their marriage, Sandy and Dorothy took many trips back to Europe. In the spring of 1984, the mayor of Le Touquet invited the couple to attend the 40th anniversary of Le Touquet’s liberation. It was a celebratory event.

“They were guests of the town. They were being honoured,” Christie wrote. “In his letter, the mayor remarked that he was sure they would remember the day of the liberation. This got a chuckle. Sandy and Dorothy knew each and every detail as if it were yesterday.”

Christie, who by 1984 was a married mother of three, joined her parents in Le Touquet with her son, Benji, who was then nine years old. Dorothy was pleased that one of her grandchildren could visit her home community and represent the next generation of her family. Sandy and Dorothy were also pleased to have an opportunity to visit with the residents of Le Touquet.

“Sandy had brought with him a bilingual commemorative scroll from Premier Grant Devine of Saskatchewan. He stood and made his presentation to the town in what he knew was ‘hesitant and appalling’ French, with Dorothy’s coaching from behind,” Christie wrote.

“Then Dorothy did something she’d never done before. To her family’s utter astonishment, she made a speech. Her audience, certainly, was demanding it. There might have been a tear in her eye, but her voice was clear. Her words flowed for five minutes of gracious memory and gratitude.”

Later in their retirement, Sandy and Dorothy relocated to Victoria, B.C., but Le Touquet was never far from their minds. In the fall of 1996, they called Christie to let her know that, when they passed away, they would like to be buried there.

“There was just one place they belonged together for eternity—Le Touquet,” Christie wrote.

As Sandy lay dying in 2003, he held Dorothy’s hand and said to his wife of nearly 60 years: “See you in Le Touquet.” Dorothy died less than two years later in Calgary, where she moved after her husband’s death to be closer to family. As they had requested, Sandy and Dorothy’s ashes were buried beneath a marble statue in Le Touquet’s cemetery, beside Dorothy’s parents.

Earlier this year, in September 2024, Christie was honoured to be invited to Le Touquet to celebrate the 80th anniversary of the Canadian liberation of the French town. She brought with her copies of her new book, and the town’s residents welcomed her and her family members with open arms.

It was an amazing experience for Christie, who recounted it in a blog post.

“After Mayor Fasquelle delivered a somber message detailing the loss and devastation that occurred in Le Touquet, we were transported—by Jeep again, of course—to another traffic circle about a kilometre away, at the corner where my mother’s childhood home, Rosemary Cottage, still stands. She lived there with her parents throughout the war years. The town had reached out to the present owners of Rosemary Cottage, who allowed their home and garden to play an authentic role in the reenactment of our parents’ first meeting.

“As the story goes, my mom vowed early in the war that she would kiss the first Allied soldier she saw. She told her plan to the female political prisoners who were in jail with her in 1942. And after five long years of wartime occupation of Le Touquet, the day after German forces fled the town, my mother heard a Jeep on the road... and the rest is history, told in my book.”